A generation of mentors continues to fade with Jimmy Dupree’s passing

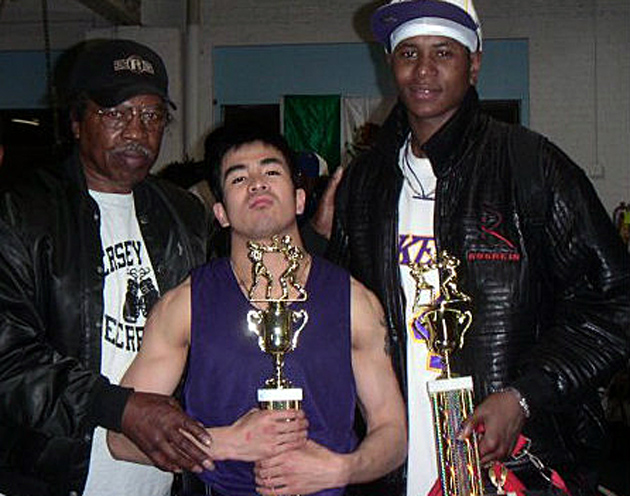

(Left to right) Former light heavyweight contender Jimmy Dupree with two of his young boxing pupils, JV Tuazon and Tyrell Wright. Tuazon won two Golden Gloves titles under Dupree before becoming a doctor; Wright is an unbeaten pro with a 4-0 (3 KOs) record.

On a bleak stretch of road in a section of Jersey City, N.J., known as The Hill, there once existed a boxing gym that offered the neighborhood youth a way to get in shape, learn a valuable skill and – most importantly – a way to stay out of trouble.

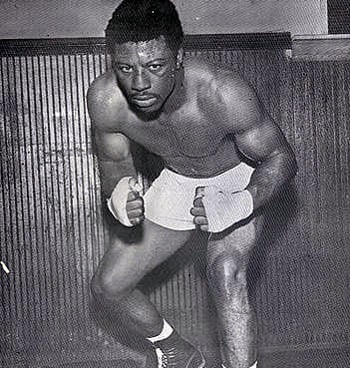

The place was called Dupree’s World Boxing Gym. Its owner was former light heavyweight contender Jimmy Dupree, whose deft reflexes earned him the nickname “The Cat” during the 1960s and early ’70s.

Dupree finished his career in 1974 with a record of 40-10-4 (24 knockouts), winning the NABF title and earning a spot in THE RING’s light heavyweight top ten ratings.

According to the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame, Dupree became interested in boxing as a 15 year old after he listened to the Joe Louis-Ezzard Charles fight on the radio in 1950 and “felt vibrations.”

His career began at the St. Nicholas Arena during its dying days as the preeminent club fight venue in New York, and led to him fighting around the country and even challenging Vicente Rondon in Venezuela for the WBA title in 1971, where he lost in six rounds.

The gym closed in 2009 after 38 years following his retirement from the Jersey City Department of Recreation. Despite his old age, Dupree never stopped conspiring to reopen its doors. “He was hurt,” recalls his daughter Pearline Dupree. “That gym was his everything.”

With Dupree’s passing on Jan. 25 at the age of 77 from Alzheimer’s Disease, his dream of reopening the center will never be realized. But the world lost more than just a gym and a trainer: it lost a mentor who gave freely in a time that isn’t given to selflessness.

I first walked into the gym at age 15. I was a teen who had boxed at the rival Union City Boxing Club, but was interested in learning from a local legend. When I told him I didn’t have the requisite $30 a month gym fee, Dupree deferred the payment until I was able to pay.

This wasn’t your modern boxing gym, where you’re more likely to find sound legal or tax advice than an actual fighter. This was Martin Luther King Drive, one of the roughest neighborhoods in Jersey City. The sound of the speed bag pounding against the support mixed in with the omnipresent Hot 97 radio tunes, and during the summer Dupree would sell crabs out in front.

Dupree preached the importance of roadwork, but he also lived it. He would organize charity runs to raise money for children with birth defects and blood drives and became known as “the man who runs for a cause.”

“He did things for the community as if they where his own family,” said Pearline Dupree. “He only wanted the best for anyone he came in contact with. If they needed something done they knew who to go to.

“He liked for the kids in the community to learn new things and go new places, even with his students. At one point he had a fishing program through the city. He was firm, sometimes mean but nice at same time. He meant good.”

Dupree spoke out of a low grumble that hinted at his South Carolina upbringing. Still, he wouldn’t hesitate to raise his voice if he felt you were wasting his time with a poor effort. He commanded the respect of his pupils, many of whom had been to jail or were known local troublemakers.

Much of that had to do with Dupree’s aura. Though in his mid-60s, Dupree still cut an imposing figure in any room, and was in better shape than most of the boxers half his age.

And when troublemakers came around to entice his fighters back to the streets, Dupree had no problem dealing with them.

JV Tuazon, who won two N.J. Golden Gloves titles under Dupree and fought briefly as a professional before becoming a doctor, recalls one such incident.

“I remember coach when he was in his late 60s, just after his neck and back surgeries,” Tuazon said. “I got to the gym and saw some blood on the floor and coach sitting unscathed with ice on his hand. All the kids were like ‘You missed it.’

“It turns out coach just knocked out a heavyweight amateur boxer who was in his 20s. The guy was a feared and well-known drug dealer in the area. Coach told me he would never let anyone bring drugs and guns around ‘his kids.’ He was just protecting ‘his kids.’

“I remember him literally telling kids to get off the corner, asking them to get off the streets and asked them what they were doing with their lives. He was real, a man of the people. That’s why he could walk around that neighborhood amongst drug dealers and killers and be respected.”

Dupree loved to recount the glory days of his boxing career, speaking of his knockout of perennial contender Johnny Persol in 1969 fondly while bemoaning that he never got a crack at then-division kingpin Bob Foster, whom he had previously sparred with.

“I was a boxer-puncher,” Dupree once told me. “I could box and I could punch. And I could get you either way.”

Dupree never produced a world champion. His highlight as a trainer was perhaps when he led an underachieving local kid named Willie Palms to the U.S. National Championships super heavyweight title in 1997. He also trained former two-time world champion James “Buddy” McGirt towards the end of his career.

But his legacy wasn’t in the number of Golden Gloves champions he produced, but in the number of lives he saved. After one summer afternoon training session in 2003, one amateur told me about how the gym and Coach Dupree were the only things that kept him out of jail and off the streets. I had always figured that most felt the same way.

“He believed in those who didn’t believe in themselves,” said Pearline Dupree. “He gave back when he could and never wanted anything back. Money was never an issue.

“The coaches of the inner city boxing gyms in Jersey City today were taught by my Dad, so his legacy will never die and will always live through them. They are also now changing lives because he changed theirs.”

Dupree’s service wasn’t called a funeral, but rather a “celebration of life,” and people from their 60s down to teenagers spoke of their memories of Dupree.

“Multiple people talked about how he was their father figure, not just a boxing coach,” said Tuazon. “People talked about their father overdosing on heroin, mom high on coke, father locked up, father dead, father left their mom, but coach was there for them. They said if it wasn’t for him, they’d be in the same place – locked up or dead. They credited him for making them men, not just boxers.”

There’s a saying among trainers today: “There’s no money in training boxers.”

That’s true, as training a lawyer or accountant will yield immediate profits while grooming a fighter from a disadvantaged background is an investment with no guarantee of paying off in the long-run.

Dupree never looked at it like that. His satisfaction seemed to come in that glimmer that came through his glasses when a student parried a jab the way he had taught him and countered with his own, or when one of them won a fight against a rival gym at a local smoker event.

A year or so after the gym closed down, I took a ride on the NJ Transit 87 bus through Martin Luther King Drive to survey my old neighborhood. Once upon a time there was a glimmer of hope that shone through the gritty neighborhood of boarded-up buildings and makeshift business shops.

The beacon was gone, and only a void remained.

Photo / the Dupree family

Ryan Songalia is the sports editor of Rappler, a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America (BWAA) and a contributor to The Ring magazine. He can be reached at [email protected]. An archive of his work can be found at ryansongalia.com. Follow him on Twitter: @RyanSongalia.