Hands of Stone: 10 fights that cemented Duran’s legend – part I

More than 11 years after officially announcing his retirement, Roberto Duran’s career inside the ring will experience a “full circle moment.” On Sept. 7, the 62-year-old icon is scheduled to box a three-round exhibition inside Buenos Aires’ legendary Luna Park against former middleweight titlist Jorge Castro, who, at age 46, is using the event to bid his own farewell to boxing.

That the event is taking place in Argentina is significant, for it was there on Oct. 3, 2001, that Duran was involved in the car crash that would lead to the end of his extraordinary 33-year career. He was there to promote a salsa CD and was traveling with his son Chavo and two reporters when the accident occurred. Duran suffered multiple injuries that included broken ribs and a collapsed lung and when his recovery proceeded more slowly than he wanted he knew his in-ring journey had come to an end.

“I can’t return to fight anymore because (the recovery process) is going to take a lot more time,” Duran said then.

Duran was correct, for it took his body quite a while to regain its pre-accident state. However, there were other wounds – spiritual wounds – that never fully healed. The accident prevented Duran from ending his career entirely on his own terms, and given his robust pride that fact surely had to bother him.

Perhaps this appearance will allow Duran to achieve the peace he needs to walk away from in-ring combat – once and for all.

In terms of time, place, opponent and parameters, this event appears to be the perfect way for Duran to leave. It’s not an official fight but rather a public sparring session, so the proceedings will be tightly controlled in terms of inflicted punishment. Also, the exhibition will allow the crowd the luxury of paying tribute to both men instead of choosing sides as was the case in their February 1997 bout won by Castro in Argentina and the rematch won by Duran in Panama City four months later.

Once Duran exits the ring we all will be left to savor his legend one last time – and what a legend it is. The third man ever to capture major titles in four weight classes (only Thomas Hearns and Sugar Ray Leonard preceded him), Duran amassed a 103-16 (70) record and assembled a resume that included a then-record 10 consecutive knockouts in world title fights, enshrinement in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2007, nearly universal recognition as a top-two all-time lightweight and a consensus top-10 ranking in boxing history’s pound-for-pound list.

Once Duran exits the ring we all will be left to savor his legend one last time – and what a legend it is. The third man ever to capture major titles in four weight classes (only Thomas Hearns and Sugar Ray Leonard preceded him), Duran amassed a 103-16 (70) record and assembled a resume that included a then-record 10 consecutive knockouts in world title fights, enshrinement in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2007, nearly universal recognition as a top-two all-time lightweight and a consensus top-10 ranking in boxing history’s pound-for-pound list.

Not only was Duran a fantastic fighter, his persona was unlike any other because while his appearance – and our perception of him – changed over time, he possessed a competitive streak that was undeniable and a personality that was magnetic.

As a young lightweight, Duran was a tightly-coiled, fire-breathing aggressor who knocked his opponents back into the Stone Age with his “Hands of Stone.” As he matured, Duran added subtle defensive wrinkles to his game and expanded his offensive weaponry to the point that he became a strategic wizard. Following the infamous “No Mas” fight in his second bout with Sugar Ray Leonard in November 1980, Duran became a sympathetic figure capable of suffering great falls as well as summoning magical resurrections. As he fought deeper into his 40s Duran became a professor emeritus whose guile still allowed him to win more often than not. And now, as he prepares to enter the ring in Buenos Aires, Duran is a walking, talking monument to fistic greatness.

The following list will relive 10 of Duran’s greatest performances in terms of execution, circumstance and level of opponent. For the younger generation it will serve as a primer as to why he is so highly regarded by their elders while for older readers it will allow them to re-live the high points of a supremely unique athlete.

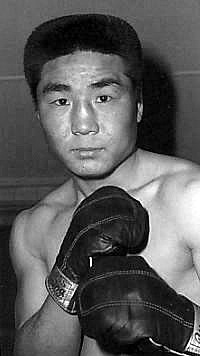

10. Oct. 16, 1971 – KO 10 Hiroshi Kobayashi, Gimnasio Nuevo Panama, Panama City, Panama

Just 34 days after an electrifying 66-second knockout of Benny Huertas in his Madison Square Garden debut, the 20-year-old Duran returned home to take on his best opponent yet in terms of world-class experience.

Up until three months ago, the 27-year-old Kobayashi had been a two-time 130-pound titlist who, during a  four-year tenure that began with a 12th round KO of Yoshiaki Numata, defeated Antonio Amaya twice, drew with Rene Barrientos and out-pointed future titlist Ricardo Arrendondo, whose younger brother Rene would win a 140-pound belt more than a decade later. His 61-9-4 (10) record illustrated his great experience but also exposed a severe shortcoming – a lack of world-class punching power.

four-year tenure that began with a 12th round KO of Yoshiaki Numata, defeated Antonio Amaya twice, drew with Rene Barrientos and out-pointed future titlist Ricardo Arrendondo, whose younger brother Rene would win a 140-pound belt more than a decade later. His 61-9-4 (10) record illustrated his great experience but also exposed a severe shortcoming – a lack of world-class punching power.

Kobayashi entered the Duran fight on a down note, for the classy Venezuelan Alfredo Marcano dethroned him with a come-from-behind 10th round knockout in Aomori, Japan. Kobayashi hoped beating Duran on Duran’s home turf in his lightweight debut would earn him an immediate crack at either WBA titlist Ken Buchanan or the winner of the following month’s WBC title fight between Mando Ramos and Pedro Carrasco, which was to be held in Carrasco’s native Spain.

The battle lines couldn’t have been more stark: Kobayashi’s plan was to use his technical skills to pick Duran apart and pile up points while Duran’s was to exert pressure and crack Kobayashi with his “hands of stone,” a nickname inspired by the Huertas demolition.

Interestingly, it was Kobayashi who landed the fight’s first hard punch. A hook to the jaw drove Duran back a couple of steps and let him know he was in with a higher class of fighter. Duran received that message loud and clear, then acted accordingly. Duran trapped Kobayashi on the corner pad and bombed away but the Japanese got in several quick counter rights to the face as well as a stunning hook that had Duran holding on. But Duran recovered quickly and he ended the high-energy first round by landing a hard one-two to the face.

Armed with the proper respect, Duran operated from longer range in the second and proceeded to land spearing jabs and sharp powerful counters over Kobayashi’s wilder swings. Duran also ducked under and pulled away from Kobayashi’s spurious offerings and he capped the round by landing two robust rights.

Duran seized command of the fight starting in the third as his quicker hands sliced through Kobayashi’s guard. The variety of Duran’s attack was impressive for someone so young and at one point he blasted through three consecutive right uppercuts. The heat and humidity also were taking a toll on the ex-champ and Duran’s rights raised a swelling over Kobayashi’s left eye. The younger Duran exerted subdued but ceaseless pressure while Kobayashi resorted to fighting in spurts.

By the sixth Duran was in full command and he let everyone know how confident he was by rolling his hands and upper body, bouncing on his toes and smacking Kobayashi at will from numerous angles. While Kobayashi managed to land counters from time to time, they lacked sufficient force to bother Duran.

Going into the seventh Duran led 59-57 on the scorecards of referee Isaac Herrera and judge Harmodio Cedeno while judge Juan Carlos Tapia had Duran tossing a 60-56 shutout. It was here that Duran decided to put the hammer down. A lead right to the chin was immediately followed by a flush left-right to the face that swiveled Kobayashi’s head and caused the best of his body to spin to the canvas. With the local crowd screaming themselves hoarse, Kobayashi could do no more than roll meekly onto his side by the time Herrera counted him out at the 30-second mark.

The Duran fight was fated to be the last of Kobayashi’s career, but his conqueror would go on to climb – and conquer – far higher summits.

9. March 2, 1975 – KO 14 Ray Lampkin, Gimnasio Nueva Panama, Panama City, Panama

As Duran closed in on his 24th birthday, he was approaching the peak of his powers. As a fighter there were few better pound-for-pound, as his 48-1 (41) record suggested, but he also was growing into his savage persona. The seasoned Duran was now a sneering, swaggering force of nature that sported a lean, mature, athletic physique and a Manson-esque stare that shook opponents to their cores. When Duran chose to wear a goatee, his visage was almost satanic, though his opponents would argue that Duran was the real thing.

Going into this fight Duran was on a knockout tear; he had stopped his last four opponents and his last three in the first round. One of that unfortunate trio was title challenger Masataka Takayama, who suffered three knockdowns before being flattened in 100 seconds.

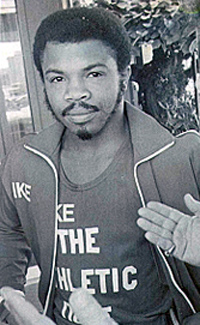

Standing in the other corner was Ray Lampkin, a talented 27-year-old Oregonian who came into the fight with a 29-3-1 (12) record. Interestingly, Lampkin’s world-class credentials were shaped by two 12-round defeats to Esteban DeJesus. In the first fight in Puerto Rico, Lampkin overcame a first-round knockdown and a slippery canvas to last the distance while the rematch at New York’s Felt Forum saw Lampkin lose a hotly disputed decision despite fighting with inflamed gallstones.

Standing in the other corner was Ray Lampkin, a talented 27-year-old Oregonian who came into the fight with a 29-3-1 (12) record. Interestingly, Lampkin’s world-class credentials were shaped by two 12-round defeats to Esteban DeJesus. In the first fight in Puerto Rico, Lampkin overcame a first-round knockdown and a slippery canvas to last the distance while the rematch at New York’s Felt Forum saw Lampkin lose a hotly disputed decision despite fighting with inflamed gallstones.

Despite the defeats, Lampkin proved to himself he could compete at the highest levels. Since losing the DeJesus rematch, Lampkin had won six straight and along the way he captured (and defended twice) the NABF lightweight title. Although he had to fight the fearsome champion in his home country, Lampkin had reason to feel confident. First, speedy boxers like DeJesus and Ken Buchanan threw off Duran’s timing and second, if DeJesus could beat Duran, why can’t he?

“They were trying to make Duran out to be this Superman character,” Lampkin told author Christian Guidice in the Duran biography “Hands of Stone,” “He was human, and when you cut him, he bled, just like I did. They were acting like he couldn’t be beat, and I saw Esteban do it. They tried to intimidate me and tell me that if I beat Duran, I probably wouldn’t leave there alive. I told them that if I die, then I would be a dead champion, because if I beat him they were going to have to kill me.”

As was usually the case, the outdoor arena was awash in heat and humidity, conditions that only amplified the advantages Duran enjoyed. But Lampkin opened the bout positively; he boxed well enough to establish his long-range game yet slugged often enough to show the champion he was willing to engage. In round two, the feisty Lampkin dug several hard rights to Duran’s ribs, then won a wild exchange at ring center as the ringsiders roared.

The pair set a torrid pace with Duran moving forward behind fast, power-laden punches and Lampkin engaged in purposeful retreat. Duran appeared to have an edge through the early rounds but Lampkin hung tough and fired back whenever possible. But it was apparent that Lampkin’s best right hands lacked the steam to move Duran and that fact guaranteed a long, hard slog would be necessary to pull the massive upset.

It wasn’t to be. Duran’s ceaseless pressure and superior firepower gradually wore down the challenger, who nevertheless continued to battle despite his deterioration. Duran picked up steam in the bout’s second half and by the 12th Lampkin sported a mouse under the left eye and a weary expression. By answering the bell for the 12th Lampkin achieved a victory of sorts by passing DeJesus as Duran’s longest-lasting challenger to date and though he was clearly tired it appeared his fighting heart might be enough to carry him the entire 15 round distance.

Duran had other ideas – frightening ideas. Less than 30 seconds into the 14th Lampkin moved toward the ropes, where Duran whipped over a whistling hook that connected flush with the challenger’s jaw. Lampkin fell back first and his head hit the canvas with sickening force. There was no getting up for Lampkin and the aftereffects were harrowing – Sports Illustrated reported Lampkin was out for 80 minutes (Giudice’s book indicated 30 minutes) and that the challenger was hospitalized for five days. One media report indicated that Lampkin had died but while Lampkin was (and still is) alive and well, the fall did leave his left leg temporarily paralyzed.

After the bout Duran uttered one of his most famous – or infamous – quotes: “I was not in my best condition. Today I sent him to the hospital. Next time I’ll put him in the morgue.”

The quote fit the deed, for the Lampkin knockout was arguably the most damaging, sensational one-punch knockout of Duran’s career.

8. Jan. 21, 1978 – KO 12 Esteban DeJesus III, Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, Nevada

After of years of weight-making struggles, Duran was ready to end his majestic six-and-a-half year reign and sample his wares in other divisions. But before he did so he had one final piece of business to address – settling the score with Esteban DeJesus once and forever.

To date, DeJesus had inflicted the only loss of Duran’s 63-fight career in a non-title 10 rounder in December 1972 while Duran returned the favor by recording DeJesus’ first defeat in their March 1974 rematch with Duran’s title on  the line. Since then, DeJesus won the WBC belt by stopping Ishimatsu “Guts” Suzuki and recording three defenses against Hector Medina (KO 7), Buzzsaw Yamabe (KO 6) and Vicente Mijares (KO 11), all the while baiting Duran verbally. As for Duran, he gave back in kind and wanted nothing more than to shut DeJesus’ mouth as well as break the mandible that controlled it.

the line. Since then, DeJesus won the WBC belt by stopping Ishimatsu “Guts” Suzuki and recording three defenses against Hector Medina (KO 7), Buzzsaw Yamabe (KO 6) and Vicente Mijares (KO 11), all the while baiting Duran verbally. As for Duran, he gave back in kind and wanted nothing more than to shut DeJesus’ mouth as well as break the mandible that controlled it.

The stakes couldn’t be higher; the undisputed lightweight title was on the line, a belt that hadn’t been unified since 1971, but moreover it would determine each man’s place in history. Like the great trilogies of the past, the man who ended up with the lead would be thought of as the better fighter and neither man’s pride would tolerate anything less than total victory.

Each fighter achieved his first major win by making weight. DeJesus scaled 134 while Duran was 134 1/4, and while Duran had to take off 15 pounds in the final four weeks it was DeJesus who worked until the last possible minute to squeeze out the final ounces. The already tense personal dynamic then boiled over when a scuffle broke out between the fighters and their camps.

Given Duran’s volcanic temper – and the violent way he dealt with DeJesus in their second fight – most observers expected the fiery Panamanian to overwhelm his Puerto Rican rival with brute force. At the urging of trainers Ray Arcel and Freddie Brown, however, Duran chose to box patiently at long range, and, to the shock of virtually everyone, they even touched gloves at the opening bell.

Duran’s first punch, a stabbing jab, smacked off DeJesus’ face and the WBC titleholder responded by flashing a wry grin. Duran’s powerful lefts spawned blood from DeJesus’ nostrils in less than 90 seconds’ time while the smirking Puerto Rican’s jabs barely registered with the stone-faced Duran. When the bell sounded Duran achieved a personal victory by avoiding a left-hook knockdown, which DeJesus achieved in each of their first two fights and to this point marked the only such events in Duran’s career.

In round two Duran’s coal-black eyes intensely scanned for openings while his arms seized upon them. Meanwhile, DeJesus continued to probe with long, flicking jabs and strike with unusually wide punches.

The action heated up in the third as DeJesus began finding the range with right hands and Duran invested more power behind his shots. A robust Duran right to the body sparked an intense exchange at ring center in the round’s final minute.

DeJesus was known as a supreme ring technician but as the rounds continued to fly by Duran proved he was every bit the scientist DeJesus was – and more. His vast array of defensive maneuvers set up his prodigious offensive strikes and Duran’s clinical precision in terms of executing strategy stood in stark contrast to his combustible reputation. His razor-sharp intellect pounced on every tactical error DeJesus made and the audience marveled at the scope and impact of Duran’s consequences. Duran took full control in the sixth as he worked up and down DeJesus’ anatomy and rattled him with well-timed combinations. A bruise sprouted under DeJesus’ cheek and by the seventh the WBC titlist was in survival mode.

Lacking the one-punch power to stop Duran’s attack, DeJesus was forced into an untenable position. Still, DeJesus’ courage and stubbornness wouldn’t let him quit even as his gas tank emptied and ran on fumes. Because of that, Duran was able to show the world just how sophisticated a fighter he had become since mauling Ken Buchanan all those years ago.

Duran upped the ante in round nine with several hard body shots, pushed his chips toward the center in rounds 10 and 11 and forced DeJesus to fold in the 12th. An explosive lead right to the temple floored DeJesus and forced him to crawl across the ring to find a friendly strand of ropes from which to haul himself up by six. Duran then landed 11 straight power punches, the last of which forced a thoroughly hurt and exhausted DeJesus to take a seat on the canvas. At 2:32 of round 12, Roberto Duran joined heavyweight Muhammad Ali and middleweight Rodrigo Valdes as boxing’s only undisputed champions but more importantly to Duran, he had established undisputed superiority over his greatest lightweight rival.

“I cannot erase the loss,” Duran said afterward. “But tonight I erased DeJesus.”

7. June 22, 1979 – W 10 Carlos Palomino, Madison Square Garden, New York, New York

After uniting the lightweight titles against DeJesus, Duran immediately gave them up in pursuit of welterweight glory. He used the next four fights against Adolfo Viruet (W 10), Ezequiel Obando (KO 2), Monroe Brooks (KO 8) and 91-fight veteran Jimmy Heair (W 10) to adjust to his new class as his weight fluctuated between 142 (Viruet) and 151 (Obando). These performances – as well as his reputation – vaulted Duran up to number two in the WBC rankings. That, in turn, positioned Duran for a crack at either longtime WBA champion Pipino Cuevas or the winner of November’s meeting between WBC king Wilfred Benitez and challenger Sugar Ray Leonard. But before Duran could think about adding a second divisional title, he had to get past number-one rated challenger Carlos Palomino.

Up until this past January, Palomino had been the WBC’s champion, and during his two-and-a-half year reign he proved himself a fitting representative as five of his seven defenses ended inside the distance. Until Benitez dethroned him in his most recent fight by a split decision that most thought should have been unanimous, many observers believed he had the talent to defeat the fearsome Cuevas in a mythical head-to-head duel.

Up until this past January, Palomino had been the WBC’s champion, and during his two-and-a-half year reign he proved himself a fitting representative as five of his seven defenses ended inside the distance. Until Benitez dethroned him in his most recent fight by a split decision that most thought should have been unanimous, many observers believed he had the talent to defeat the fearsome Cuevas in a mythical head-to-head duel.

Palomino was a physically strong welterweight who used a formidable body attack to wear down opponents. Usually a slow starter, Palomino often found himself down on the cards early only to come on strong down the stretch, as was the case in his title-winning effort against John H. Stracey, his first defense against Armando Muniz and his second defense against Dave “Boy” Green. For Palomino, his stamina and stout chin were as much weapons as his hefty hook.

Unlike most champions who start young in the sport, Palomino was a semi-pro baseball player who didn’t begin his amateur boxing career until age 21. He was an All-Army champion in 1971 and 1972 and on his way to winning the 1972 AAU title he defeated Sugar Ray Seales, who went on to win the gold medal at the Olympics in Munich later that year. He also was one of boxing’s rare college graduates, for he earned a degree from Long Beach State.

While Palomino loved boxing, it didn’t consume him. Long before he lost the title to Benitez he declared he would retire by age 30 to pursue a career in acting. By the time he met Duran, he was two months shy of that landmark birthday so for Palomino it was now – or never.

At 145¼, Duran’s body was markedly thicker than during his lightweight days but happily for him he still possessed blazing hand speed. Advancing behind subtle head and shoulder feints, Duran made a positive first impression by landing a strong hook to the jaw. He then moved inside and engaged Palomino in a test of strength, a test that saw him pass with flying colors as he pushed the bigger man back with his forearms and shoulders and punched him with blows hard enough to earn respect.

At 145¼, Duran’s body was markedly thicker than during his lightweight days but happily for him he still possessed blazing hand speed. Advancing behind subtle head and shoulder feints, Duran made a positive first impression by landing a strong hook to the jaw. He then moved inside and engaged Palomino in a test of strength, a test that saw him pass with flying colors as he pushed the bigger man back with his forearms and shoulders and punched him with blows hard enough to earn respect.

By the second round Duran already was bathed in sweat and he was in a fighting froth. He repeatedly beat Palomino to the punch with hair-trigger shots before he could even react. Two searing uppercuts jerked Palomino’s head late in the round and by round’s end his cheekbone was noticeably puffy.

A lazy jab was all Duran needed to land a cracking one-two in the third, after which he bulled Palomino to the ropes and connected with a four-punch salvo to the head before locking on a clinch. By winning the small skirmishes, Duran was piling up enough points to win the bigger war. It soon became clear to all that Duran was the great little man and that Palomino was merely a very good bigger man. Palomino’s successes were infrequent – a jab to the face in round four that drew a wolfish smile and mini-rallies in rounds five and seven – but he never quit trying to reverse the tide.

Duran’s power-punching credentials at 147 were solidified seconds into round six. Even before chief second Ray  Arcel could leave the ring apron, a scorching right to the chin caused Palomino to topple to the floor. It was only the second knockdown of Palomino’s 33-fight career and the ex-champ had to call upon every resource to keep his feet for the remainder of the round. Palomino paid a price for his toughness, for Duran opened small cuts on the corner of the right eye as well as his left ear, but late in the round Palomino strung together his best combination of the fight – a one-two followed by a left hook-right uppercut.

Arcel could leave the ring apron, a scorching right to the chin caused Palomino to topple to the floor. It was only the second knockdown of Palomino’s 33-fight career and the ex-champ had to call upon every resource to keep his feet for the remainder of the round. Palomino paid a price for his toughness, for Duran opened small cuts on the corner of the right eye as well as his left ear, but late in the round Palomino strung together his best combination of the fight – a one-two followed by a left hook-right uppercut.

Duran’s counters widened Palomino’s cut in the seventh and by the ninth he was landing rights with impunity. It would have been easy for Duran to coast in the 10th but instead he finished strongly, though a bit of clowning brought a punishing reply from Palomino. At the bell a triumphant Duran fell to his knees with both arms upraised and his confidence was certified by judges Harold Lederman and Tony Castellano as well as referee Arthur Mercante Sr., all of whom had Duran a 99-90 winner.

“As you can see, I’m not what I used to be,” Palomino told HBO’s Larry Merchant shortly before the decision was announced. “I didn’t have that hard drive at the end. He was very strong and he was very quick, which surprised me. I didn’t expect that much quickness after he put on that much weight. But that’s the way boxing is. I had a great career and I have to believe this might be it.”

It was – for 18 years. Following the death of his father, Palomino launched an improbable comeback at age 47 that saw him win four of five fights between 1997 and 1998. His only loss was to welterweight contender Wilfredo Rivera in his final bout. As for Duran, further glories awaited.

6. June 26, 1972 – KO 13 Ken Buchanan, Madison Square Garden, New York, New York

Duran’s destruction of Benny Huertas in his U.S. debut achieved its goal: Raise Duran’s profile to the point that he would be the challenger for one of the lightweight titles. WBC king Mando Ramos was embroiled in a controversial, and often bizarre, three-fight series with Pedro Carrasco, so, by default, WBA champion Ken Buchanan was deemed the intended target.

But the hard-bitten Scot never was an easy target for anyone. His nimble movement, darting jabs, accurate crosses and considerable fighting heart was a tough mix for anyone and the result was a sterling 43-1 (16) record that included two victories over Duran’s countryman Ismael Laguna and a Fighter of the Year award from the American boxing Writers Association in 1970. His skills fostered an unshakable self-belief that served him well when he won the belt in San Juan and defended it in Los Angeles (W 15 Ruben Navarro) and New York (W 15 Laguna II). In fact, Buchanan was fresh off a third round TKO victory in Johannesburg over the 25-2 Andries Steyn in a non-title go two months before meeting Duran at Madison Square Garden. Make no mistake: Buchanan, who was two days away from turning 27, was at the peak of his powers and would be a demanding challenge for the 21-year-old Panamanian challenger. In fact, Buchanan was installed as a 13-to-5 favorite to turn back Duran, whose record was 28-0 (24).

But the hard-bitten Scot never was an easy target for anyone. His nimble movement, darting jabs, accurate crosses and considerable fighting heart was a tough mix for anyone and the result was a sterling 43-1 (16) record that included two victories over Duran’s countryman Ismael Laguna and a Fighter of the Year award from the American boxing Writers Association in 1970. His skills fostered an unshakable self-belief that served him well when he won the belt in San Juan and defended it in Los Angeles (W 15 Ruben Navarro) and New York (W 15 Laguna II). In fact, Buchanan was fresh off a third round TKO victory in Johannesburg over the 25-2 Andries Steyn in a non-title go two months before meeting Duran at Madison Square Garden. Make no mistake: Buchanan, who was two days away from turning 27, was at the peak of his powers and would be a demanding challenge for the 21-year-old Panamanian challenger. In fact, Buchanan was installed as a 13-to-5 favorite to turn back Duran, whose record was 28-0 (24).

Buchanan-Duran was a genuine sporting attraction and the public responded by setting a new indoor record for lightweights ($223,901 from 18,221 paying customers). Buchanan’s slick boxing and Duran’s torrential pressure made for a dynamic mix and the fighters didn’t disappoint.

Duran produced instant action as he tore from his corner and decked an off-balance Buchanan with an overhand right to the side of the head. Referee Johnny LoBianco deemed it an official knockdown but others thought it should have been called a slip. One fact was beyond argument, however: Duran was the contest’s driving force and the only questions were (1) how much could Buchanan take and (2) how long would Duran’s battery last? After all, Duran had only gone 10 rounds three times in 28 fights and had yet to see rounds 11 through 15 – rounds that were proven Buchanan turf.

The youngster’s pressure and big-time power continually threatened to overwhelm the champion, but the determined Scot gallantly – and sometimes effectively – answered Duran’s charges with straight, sharp punches and a wide array of defensive maneuvers. While Buchanan’s fortitude was admirable, it was Duran who scored the vast majority of the points. Each succeeding round was a carbon-copy of the previous one as Duran charged and Buchanan countered and by the home stretch Duran had built an unassailable lead. Under the rounds system, judge Bill Recht had Duran leading 9-2-1 while Jack Gordon had it 9-3 and referee Johnny Lobianco scored it 8-3-1.

At times, however, Buchanan’s pluck grated at Duran and the youngster occasionally resorted to foul tactics to vent his frustration. No matter how much punishment Duran dished out, the proud Buchanan refused to fall. At the end of the 13th round, the challenger’s angst reached a boiling point.

The pair was involved in a heated exchange when the bell sounded. Buchanan tossed a light right at Duran an instant after the gong and the challenger, perhaps angered by the after-the-bell action, ducked underneath and drove his own right to Buchanan’s groin as LoBianco rushed in to pull him away. The stricken Buchanan clutched his groin and writhed on the canvas before hauling himself erect and stumbling toward his corner.

LoBianco had several options. He could have disqualified Duran for the low blow. He could have given Buchanan a five-minute injury time-out with the caveat that if he could not continue after that he’d lose the title. He could have consulted the judges to see if they had seen the low blow. He could have declared a no-contest due to injury, which would have resulted in Buchanan retaining the title. In the end, LoBianco did none of these things; because he did not clearly see the foul blow and because he felt Buchanan was too injured to continue he declared Duran the TKO winner.

Duran’s final blow burst a vein in Buchanan’s right testicle and he was hospitalized in Scotland for 10 days. According to Giudice’s book, the aftermath will continue for the rest of Buchanan’s life.

“Even today the liquid doesn’t get up that way and it stops and I still get a pain there every time I go to the bathroom,” Buchanan said in Giudice’s book. “I’ll have that until the day I die. I told Roberto, ‘I’ll never forget you. Every time I take a piss I’ll think of you.'”

Duran’s scintillating performance forced boxing fans to think of the young Panamanian too, for it marked the beginning of a long, winding and often brilliant journey.

Research sources used include:

“Hands of Stone: The Life and Legend of Roberto Duran” by Christian Giudice

“In the Corner: Great Boxing Trainers Talk About Their Art” by Dave Anderson

“The Big Fight: My Life in and Out of the Ring” by Sugar Ray Leonard

with Michael Arkush

“25 Years Later: Duran vs. Moore Remembered” by Lee Groves

“A Passion Ignited: A Writer’s Thunderbolt Moment” by Lee Groves

*

Photos / THE RING

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.