Aug. 2, 1980: A day that changed boxing

With the crowd still buzzing about Hearns’ highlight-reel triumph, longtime WBA junior lightweight titlist Samuel Serrano entered the ring to defend his belt for the 11th time against Japan’s Yasutsune Uehara.

The lanky native of Toa Alta, Puerto Rico was a pure boxer that scored points with whipping jabs and pinpoint rights that were set up with constant movement. Whenever an opponent managed to get inside his enormous reach Serrano smothered him in an octopus-like grip and sometimes let go only after executing some of his sport’s darker arts.

Serrano built a record of 29-3 (7) coming into his first world title fight against WBA junior lightweight titlist Ben Villaflor in Honolulu, the Filipino champion’s adopted hometown. Most observers felt Serrano deserved the verdict but the cards revealed a split draw. The WBA ordered an immediate rematch and this time the bout was staged in Serrano’s native Puerto Rico. Six months after the disputed draw, Serrano dethroned Villaflor via a lopsided – and deserved – decision.

Serrano built a record of 29-3 (7) coming into his first world title fight against WBA junior lightweight titlist Ben Villaflor in Honolulu, the Filipino champion’s adopted hometown. Most observers felt Serrano deserved the verdict but the cards revealed a split draw. The WBA ordered an immediate rematch and this time the bout was staged in Serrano’s native Puerto Rico. Six months after the disputed draw, Serrano dethroned Villaflor via a lopsided – and deserved – decision.

Over the next four years Serrano proved to be a fighting champion willing to risk his belt on the road. Besides five successful defenses in Puerto Rico, Serrano retained his belt in Ecuador, Venezuela, Japan and South Africa. In fact, the two fights leading up to the Uehara contest saw the usually light-hitting Serrano (14 KOs in his 42-3-1 record entering the Uehara defense) Serrano scored TKOs against the 70-1-2 Nkosana Mgxaji (pronounced Ma-GOT-chee) in Capetown and Battlehawk Kazama in Nara, Japan, so when Serrano got the call to defend in Detroit against Uehara, he simply packed his bags and got on with business. It didn’t matter to him that this was his debut on the U.S. mainland as well as his first outing on American soil since the disputed draw with Villaflor; he went where the money was and on this night the money was in the Motor City.

Like most fighters, Uehara traveled a hard road to approach the summit of his sport. The son of a bath house owner, Uehara and his younger brother Seiji (better known as “Flipper”) attended Nihon University in Tokyo in the hopes of making the 1972 Olympic team. Neither sibling made the squad. Less than two years after turning pro, Yasutsune earned a title shot against Villaflor, who blasted out Uehara in a little more than four minutes’ time.

Like most fighters, Uehara traveled a hard road to approach the summit of his sport. The son of a bath house owner, Uehara and his younger brother Seiji (better known as “Flipper”) attended Nihon University in Tokyo in the hopes of making the 1972 Olympic team. Neither sibling made the squad. Less than two years after turning pro, Yasutsune earned a title shot against Villaflor, who blasted out Uehara in a little more than four minutes’ time.

Uehara shook off the disappointment by twice winning the Japanese junior lightweight title, registering eight defenses in all. Coming into the Serrano fight he had run off 10 straight victories – nine by knockout. Still, he was a massive underdog to the slick-boxing champion and few had reason to believe he’d be little more than a foil for the Puerto Rican’s polished skills.

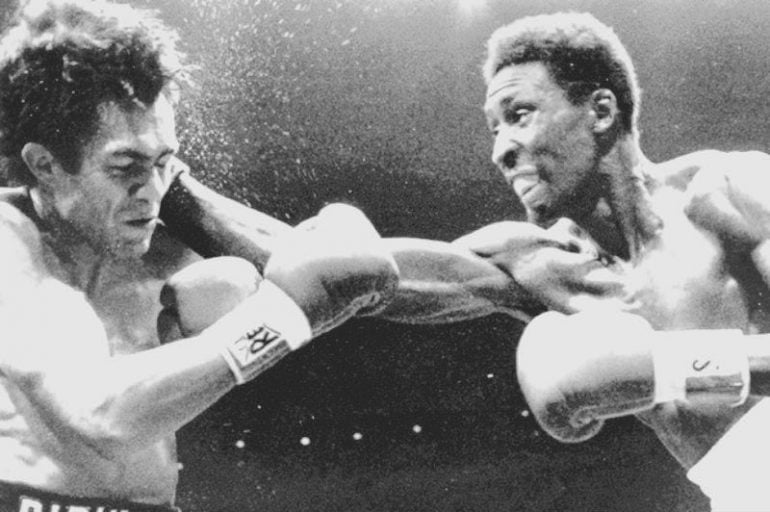

For the better part of five rounds Uehara was just that. The mantis-like Serrano cleverly used his graceful footwork and darting jabs to maintain a safe distance, occasionally landed chopping rights and slapping hooks for a change of pace and slapped on clinches nearly every time Uehara managed to close the gap. Uehara’s only moment of glory to that point came in the third round when he trapped Serrano against the corner pad and pumped away with both hands. But Serrano escaped by clinching, forcing a break and dancing back to ring center.

Serrano’s confidence grew with every passing round. Starting in round four he began putting more mustard behind his punches and late in that session he even tried a Gavilan-esque bolo punch. In round five, Serrano’s stinging right stunned Uehara and a follow-up hook to the head had the Japanese challenger holding on for the first time in the bout. After five rounds, judges Harold Lederman and Stanley Berg, along with referee Luis Sulbaran, had Serrano ahead 50-45 – the only sensible score that could be submitted given the champion’s dominance.

The sixth unfolded much like the first five had: Serrano dancing, jabbing, crossing, clinching and piling up points while Uehara doggedly — and some would say quixotically – chugging in behind power shots that sailed off target. The crowd that had been so energized by Hearns’ triumph had settled down considerably. Their barely perceptible volume mirrored the nature of Serrano’s quiet, clinical dissection of Uehara. A 15-round title-retaining decision appeared all but inevitable.

In the final minute of round six, however, Uehara produced a positive sign in the form of a lead right that caused Serrano to blink. Moments later another Uehara bull rush positioned Serrano against the ropes, where the champion landed a light hook to Uehara’s chest. Uehara, now in a southpaw stance, exploited the split-second opening Serrano’s move created with a compact right hook to the champion’s exposed jaw.

The effects of Uehara’s short, explosive punch were jarring and instantaneous. Serrano’s head snapped violently to the side, his upper body swiveled leftward and his legs crumbled like a skyscraper’s foundation under the wrecking ball. Serrano’s head lightly bounced off the canvas as it came to rest back-first on the canvas, his eyes blank and his left glove pointed toward the ceiling.

The effects of Uehara’s short, explosive punch were jarring and instantaneous. Serrano’s head snapped violently to the side, his upper body swiveled leftward and his legs crumbled like a skyscraper’s foundation under the wrecking ball. Serrano’s head lightly bounced off the canvas as it came to rest back-first on the canvas, his eyes blank and his left glove pointed toward the ceiling.

The stricken champion tried his best to get up. He lifted his head only to put it down again when the fireflies within proved too intense. He vacantly looked toward his corner before rolling onto his knees to push himself up. But by the time he strung together the necessary moves to arise, Sulbaran had already counted him out.

All of the sudden, the inevitable gave way to the improbable. At 2:59 of round six, Yasutsune Uehara became the new WBA junior lightweight champion, the final act to a most theatrical and tumultuous day.

“The incredible ending capped an equally incredible quinella which had befallen the South American powers-that-be who run the WBA over the past eight hours,” Bert Randolph Sugar wrote in his fight report in the October 1980 issue of THE RING. “Three of their most precious jewels had been lost – the junior welterweight crown to Pryor, the WBA welterweight crown to Hearns and the junior lightweight crown to Uehara. It was enough to make one swear off tequila.”

*

Photos / THE RING, CyberBoxingZone.com, ibhof.com

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.